The Artemis II mission, which will return US astronauts to lunar space, has run into problems that have critics demanding NASA remove the crew from the flight for safety reasons. The bigger question is, why do we have astronauts at all?

NASA’s Artemis program to set up a permanent US human presence on the Moon has so far cost the American taxpayer an eye-watering US$93 billion in return for, at the time of publication, only one unmanned flight around the Moon to show for it. Despite this, the Orion space capsule with its crew of four aboard is now scheduled to launch atop the SLS rocket in March of this year at the earliest.

At least, that’s the plan.

However, along with launch delays, cost overruns and questions about the basic economics of the SLS, there are calls to remove the crew of Artemis II on the grounds that the Orion spacecraft is simply too unproven and too outright dangerous for astronauts to ride in it.

After the return of the Artemis I mission in 2022, NASA engineers found that the capsule’s heat shield hadn’t burned off evenly. Instead, small chunks of the protective polymer had torn away. An official review by the NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG) said that the heat shield problems “pose significant risks to Artemis II crew safety.”

The fear is that the shield is not up to snuff and that the return of Artemis II at a speed of 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h) could cause the shield to fail catastrophically as it strikes the Earth’s atmosphere, or shoot out debris that would damage the spacecraft. If this isn’t enough, the life support system has never been flight tested. These and other issues have led some former astronauts, NASA officials, and other critics to call for Artemis II to fly without astronauts so the shield and the life support systems can be tested properly in space.

The fate of Artemis II remains to be seen, but it does raise an interesting idea. Having taken the astronauts out of the spacecraft, why put them back at all? Why do we even have astronauts?

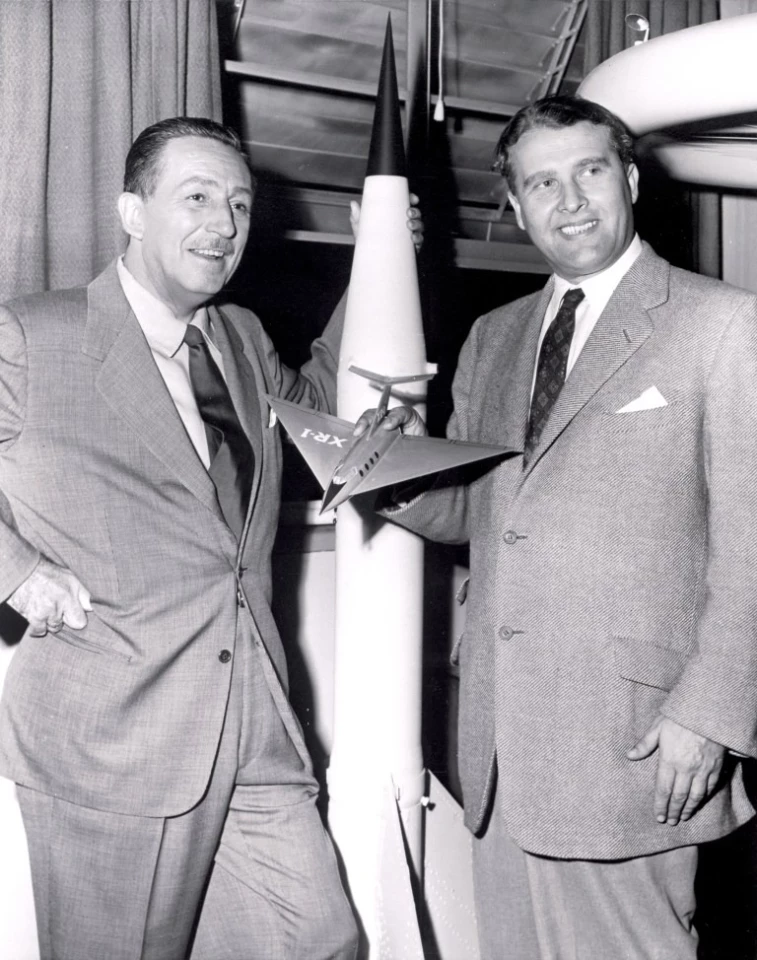

When serious plans were drawn up for the conquest of space in the late 1940s by the likes of Werner Von Braun, the question of astronauts had a simple and obvious answer – of course they’d be needed.

While the Germans demonstrated in 1942 that you could shoot a rocket into space and scientists planned to send satellites into orbit, the former was only a matter of ballistics and the latter were seen as simple, expendable instrument packages that wouldn’t last more than a few days.

NASA

For real space travel, you needed astronauts. Why? It comes down to a glass tube slightly larger than your thumb. Electronics in the 1940s were based on radio valves, also called vacuum tubes. These essentially do the same job as modern transistors. However, instead of being microscopic and embedded in a chip, these valves were incandescent filaments encased in vacuum and glass that were inches long.

These glass valves sucked up power by the hundreds of watts each and pumped out a lot of waste heat. To keep them from packing up, they had to be kept well apart from each other and provided with generous air circulation to cool them. Not that it mattered. They still packed up. It was so bad that it was a chore to keep early computers running long enough to solve a problem.

This meant was that if you wanted electronics in your spaceship or space station, you needed a small army of technicians to monitor the gear and replace the valves with monotonous regularity.

NASA

The same story spread across the whole technical spectrum. You needed pilots to fly the rockets, engineers to maintain the rocket engines and the solar power plants running on mercury steam, workers to shift cargo and dock shuttles using ropes like space dockers, more workers to dismantle spent rockets for materials, even more workers to reassemble these materials into space stations and Moon or Mars ships, and so on.

Added to this, human eyes were much better than any camera, human logic was vital in decision-making on the spot, and humans were not only better at flash calculations than early computers, they were much lighter and easier to keep than the great, clunky Univacs of the day.

Why astronauts? Because there was no alternative.

NASA

Yet that didn’t last for long. In fact, it was pretty much gone by the time the first men were shot into space. When the German V-2 rockets left the atmosphere, they were already operating at nearly the theoretical limits of chemical rockets. Increases in performance were largely a matter of scale and simplifying rocket designs to save weight.

Long story short, orbital payloads had to be kept as small as possible if the rockets of the day could lift them. Responding to this, scientists and end engineers found ways for machines to do the work that humans do. Electronics became solid state and miniaturized, computers became compact and more sophisticated at a shocking rate, spacecraft were made to pilot themselves, components assembled on Earth would dock autonomously to build stations, solar panels replaced mercury boilers, and cameras and other sensors became both more sensitive and more resilient.

By the time the Space Race played out in the 1960s, there was a perverse rivalry and interdependence between human and robotic missions.

NASA/Joel Kowsky

Space enthusiasts desperately wanted to see astronauts boldly going – preferably in Heinlein-style atomic cruisers. On the other hand, the unmanned missions were welcome as vanguards for learning more about the space environment, testing new technologies, doing reconnaissance of the Moon and planets, and even answering such basic questions like whether the Moon had a solid surface instead of a bottomless sea of fine dust.

Unfortunately for the astronaut lobby, these robots were becoming more sophisticated faster than anyone expected. By the time the Apollo program ended in 1972 and NASA’s Skylab was ready to launch, many of the reasons for sending humans into space had vanished. Spacecraft didn’t need piloting or tending. Computers could operate by themselves hundreds of millions of miles from Earth. Spacecraft could land on other planets, deploy rovers to explore, and even take readings and do chemical analysis.

In fact, in terms of astronauts, the space program was a victim of its own success. Far from opening up the Final Frontier, the Apollo Moon landing slammed it shut for the United States, which cancelled its manned Mars mission, and the Soviet Union gave up going any farther than low Earth orbit after losing the Moon Race and contented itself with small space labs.

NACA

Robotic probes proved increasingly versatile and successful, eventually visiting every planet in the solar system as well as a scattering of moons, comets, and asteroids.

Though there have been about 415 manned missions since 1961, only nine of these have traveled to the Moon and none have ventured further. Meanwhile, 146 robotic exploration missions have gone to the Moon and another 154 have gone far beyond, with five missions heading out to interstellar space, never to return.

More to the point, the robotic missions proved to be extremely successful compared to the ones involving astronauts. They were also much cheaper.

NASA

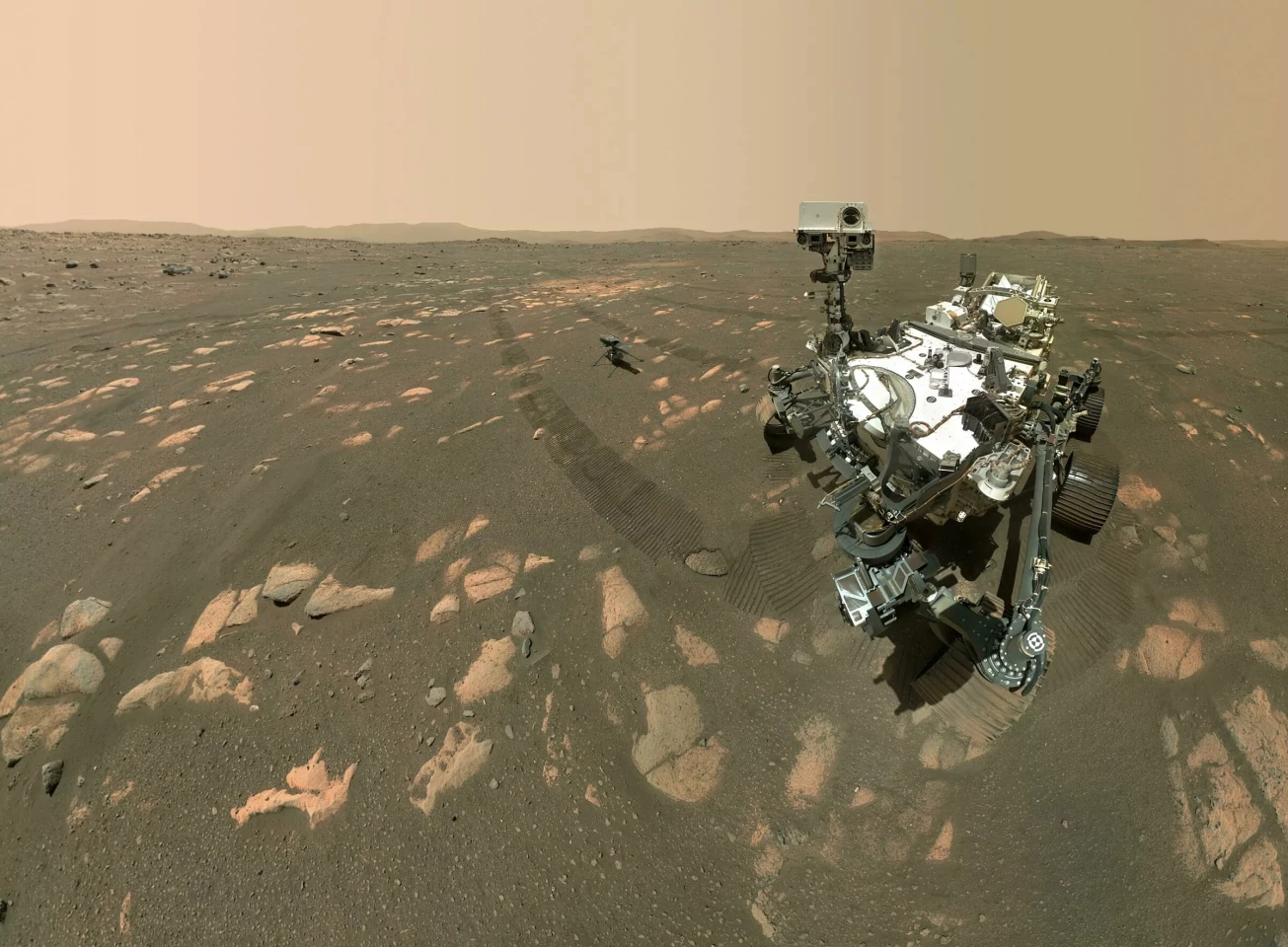

Case in point is the International Space Station (ISS). The US contribution to its costs alone is 10 times greater than those of the James Webb Space Telescope, the Cassini-Huygens Saturn orbiter, the Perseverance Mars rover, and Voyagers 1 and 2 combined. Worse, the scientific returns from the robotic missions were much more substantial than those of the ISS, whose main contributions were in space station engineering and space medicine.

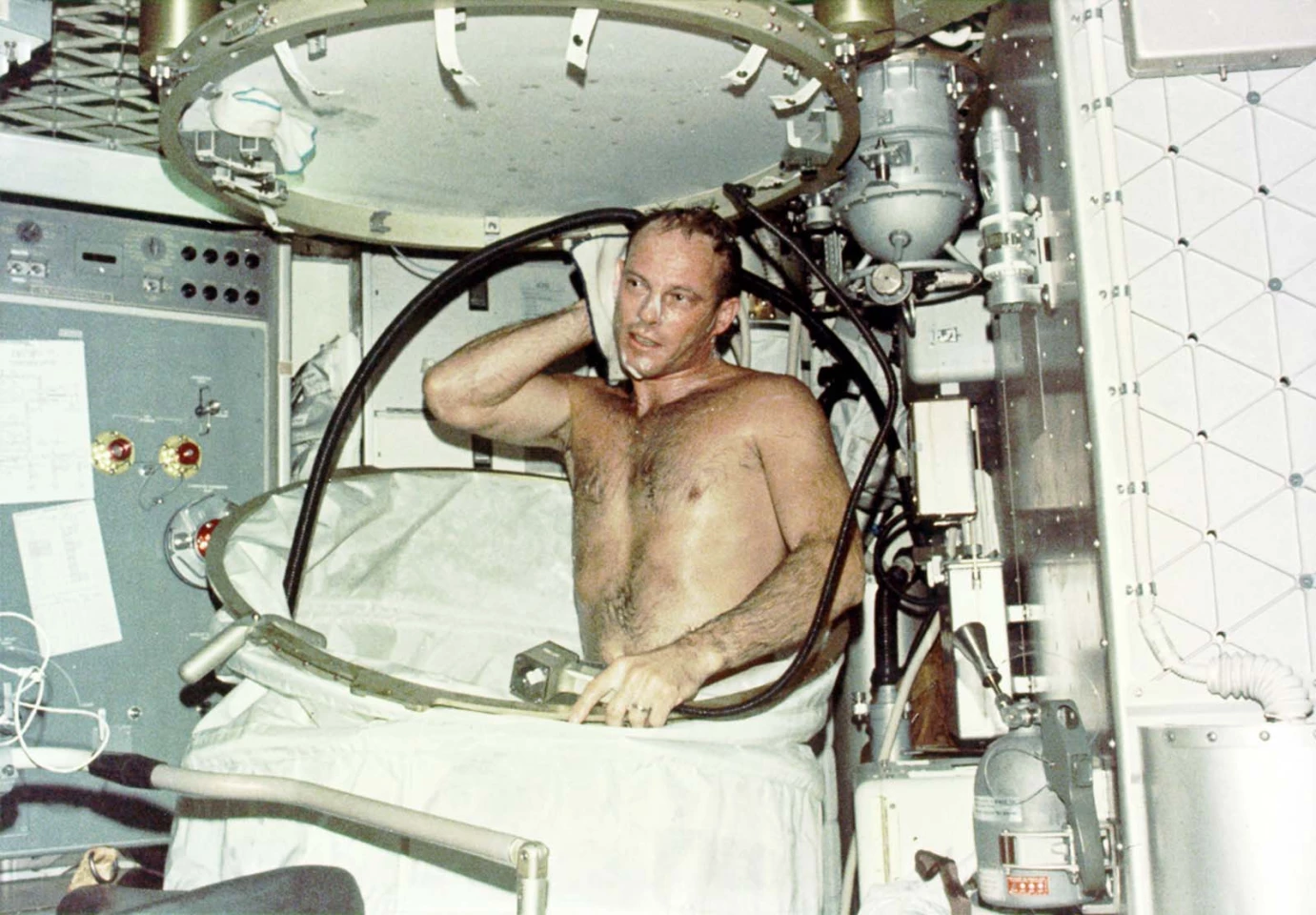

In other words, we built a space station and put astronauts on it simply to learn how to build a space station and put astronauts on it. This is a significant issue for a project intended for deep-space mission launches, microgravity research, and space manufacturing – only for it to be found unsuitable for any of those goals, largely due to the presence of the astronauts themselves.

As to its other purpose of fostering better East-West relations? That didn’t go quite as planned either.

NASA

Frankly put, the original reasons for astronauts have largely gone. Satellites, robotic systems, and modern orbital rendezvous methods have eliminated the need for humans for most tasks even in low Earth orbit. Ironically, the only place where humans are really needed is to build complex space stations like the ISS. Even then, the smaller next-generation of space stations are largely self-deploying.

True, astronauts carried out an heroic rescue of the first US space station, Skylab, when one of the solar panels and part of the heat insulating panels tore off during lift off, but if you didn’t launch a space station in the first place, there wouldn’t be any need for a rescue mission.

That’s generally the case when comparing human and robotic spaceflight. Robotic missions are cheaper, they can be tailored to meet the limitations of the current technology, and there isn’t nearly the same level of risk involved. If a manned mission fails, it’s a disaster. If a robotic mission fails, it’s a write off.

NASA

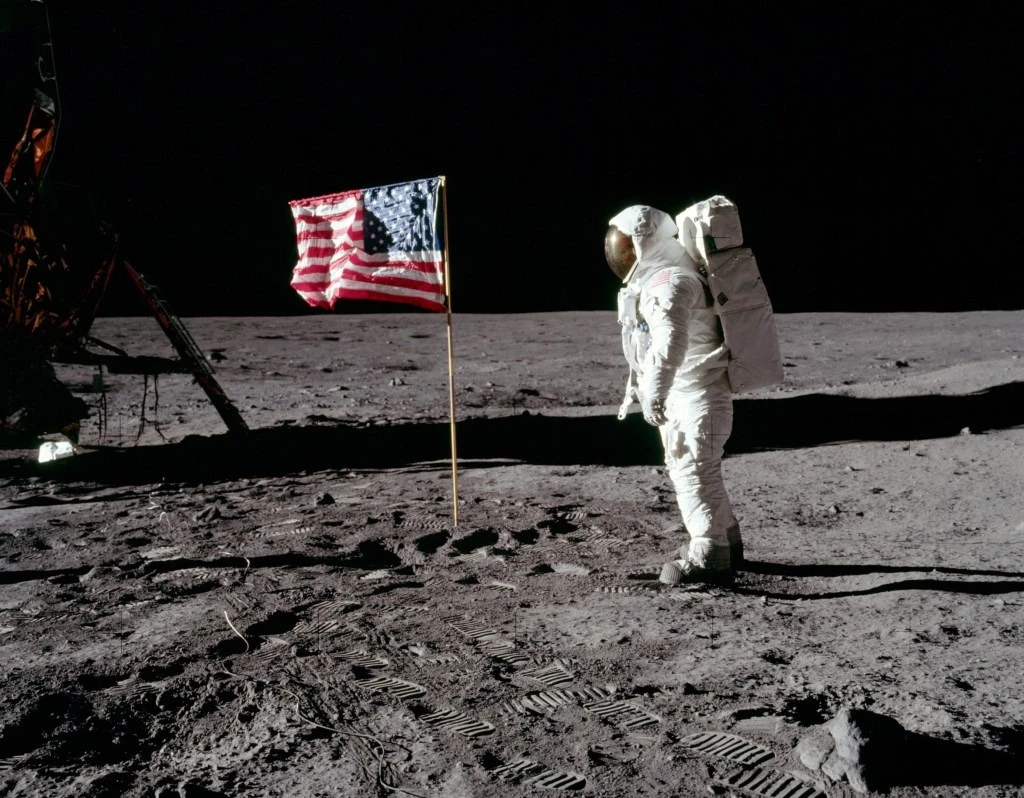

In fact, almost all robotic missions are planned as one-way affairs. No one cares if the New Horizons mission will never see Earth again now that it’s completed its historic flyby of Pluto. If Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had never returned from the Moon, it would have been cause for global mourning.

Which brings us to the fact that humans are very high maintenance and they require extremely expensive logistical support.

One thing that has been learned over the past 75 years is that space is much more hostile to humans than originally thought. In the 1950s, living in space was seen as being not much worse than being in a submarine. If you could regulate temperature and maintain a breathable atmosphere, you were good. Now we know that space has a whole raft of hazards, including hard radiation, the effects of weightlessness right down to the molecular level, and many others that still aren’t understood and could have serious long-term effects.

In addition, humans need a lot of support equipment. Aside from air, they need water, sanitary facilities, radiation shielding, exercise equipment, medical care, and a reasonable amount of privacy – not to mention laundry facilities, which the ISS has never had, so the place is a bit manky. Throw in rotating spacecraft or sections to create artificial gravity for deep space missions and you’re talking a lot of machinery and supplies.

Still, there are plans to send people back to the Moon, later to Mars, and then onward.

The question is, why?

It’s not just a question of motives.

NASA

Humans have always made incredible sacrifices for ambition. The conquest of Everest cost the lives of 13 men before Sir Edmund Hilary and Tenzing Norgay set foot on the summit. Another 18 died before the South Pole was reached by Roald Amundsen’s expedition. And the list goes on.

People also travel far and suffer great hardships in pursuit of great gains. They settle new lands. They turn wilderness into productive farmland. They seek out valuable minerals. They put to sea on great voyages to seek great fortunes or just fertile fishing grounds – often never to return.

But the key is that wise societies weigh costs against benefits.

It’s one thing to cross the road to pick up a gold ingot. It’s another thing to spend billions of dollars to mount a giant expedition to battle great odds and suffer thousands of casualties to collect a dead mouse. In every case, the game, as they say, must be worth the candle.

The problem with human spaceflight is that it is extremely expensive and dangerous, so the prize must justify all this. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon in 1969, the United States spent the equivalent of a small war and lost 10 astronauts. Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins were estimated to have only a 50/50 chance of returning to Earth alive. However, since the Apollo program was seen as a major battle in the Cold War, all this was seen as worth it.

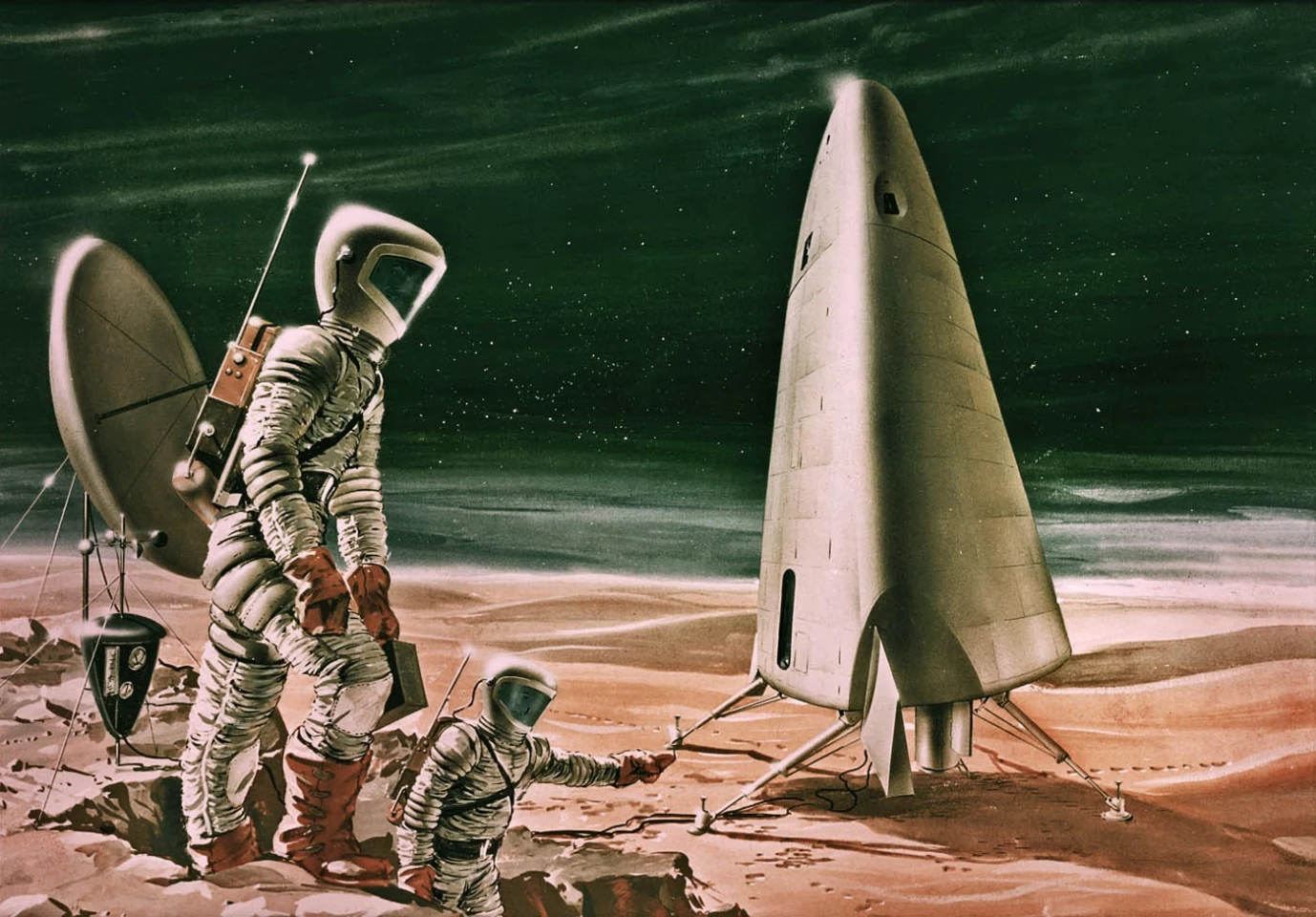

When serious space projects were first proposed, sending humans to Mars made sense. Back then, the Red Planet was regarded as marginally inhabitable. It might have sparse life such as one might see in a high-altitude desert. It was a place that humans could colonize, make habitable, and maybe even find the ruins of ancient Martian civilization.

NASA

That would certainly be something that would be worth pursuing. In reality Mars turned out to be far more hostile – an utterly dry dust ball with scarcely any atmosphere. To colonize there would be to live one’s entire life inside a tin can buried in a cave. As to life? Far from a place of scrub or even moss and lichens, let alone the remains of Tharks, the odds are now that we’d be lucky to even find fossilized bacteria.

And that is another place where humans and robots clash. If we assume that finding life on Mars is some major goal that we must strive for, it’s already been demonstrated that our machines can do the job just as well and one day maybe do it better. It simply means having more patience with our limited landers and rovers. Certainly, they would be orders of magnitude cheaper than sending astronauts and entail far less risk.

That’s the problem with human spaceflight in general. We’ve accomplished remarkable things with our machines and probes while human spaceflight increasingly becomes an exercise in human spaceflight for its own sake.

NASA

There’s nothing wrong with that. Scaling Everest cost the Hunt Expedition an estimated £470,000 (US$643,000) with very little government assistance and even ended up making a surplus through books, films, and lectures. That’s excellent for getting a couple of guys to stand on a freezing rock, and you’d have to be a killjoy to seriously object. But laying out US$500 billion for a two-year mission to reach Mars needs more than a couple of photographs to justify.

That’s the question of human spaceflight. What is the purpose of the US Artemis program? To set up a permanent human presence on the Moon? Wonderful. Why? What are they going to do? What’s the return on the huge costs and risks? To beat the Chinese? Why? The Americans did that in 1969. Rehearse for a future Mars mission? Why? For some future mining operation? Mining what? What would that entail? What would be the return? Would you need humans for that?

It’s not that there aren’t big picture reasons for human spaceflight. I can think of a number of reasons to justify it.

NASA

At the bottom it could be motivated by the needs of the human spirit, some Wellsian desire to push out to the stars. But spending hundreds and billions for an abstraction is hard to sell. It can also be argued that expanding to the stars would be an insurance plan for humanity against cosmic desire. Reasonable, but the Sun won’t die for a billion years, so there’s not much of a rush and any colony we could put on Mars would never survive on its own in the foreseeable future if the Earth suffered an extinction-level event.

None of this is to dismiss sending humans into space. Personally, I’m very keen on the idea and if someone handed me a ticket to Mars, I’d grab it – provided it was a return ticket for First Class and I passed the medical. The problem is that human spaceflight has to answer one question – why?

At the moment, there doesn’t seem to be much real purpose to launching astronauts into the void. That’s a real concern because something without a purpose is really easy to cancel. Many people are unaware that the Apollo program ended in 1964 – four years before Apollo 11. Once the objective of setting foot on the Moon was in sight, there was no compelling reason to continue. The same could happen again very easily.

So the question remains. Why?