With a chemical formula nearly identical to fictional kryptonite, unique mineral jadarite has the potential to power a million electric vehicles each year. But it remains firmly underground, beneath a picturesque valley in rural Serbia – the only place it’s been found – more than 20 years after it was discovered.

You may not have heard of jadarite, but it’s been at the center of an international battle since exploratory mining by Australian-British company Rio Tinto first unearthed this rare mineral and quickly realized its worth.

In 2004, while prospecting for borates in western Serbia’s Jadar Valley, geologists from the mining giant found something strange: A soft, white, powdery mineral that didn’t match any known records. Chemically, it’s unique – containing both lithium and boron – and so far found nowhere else on the planet. With a chemical formula of LiNaSiB3O7(OH), it’s almost identical to kryptonite.

“While lacking any supernatural powers the real jadarite has great potential as an important source of lithium and boron,” said Michael Page, a scientist from Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO). “In fact, the Jadar deposit where it was first discovered is considered one of the largest lithium deposits in the world, making it a potential game-changer for the global green energy transition.”

What Rio Tinto found beneath the sleepy valley was Europe’s largest deposit of lithium, and the company believed it could extract 2.3 million tonnes of it, which would power a million cars for a few decades. What’s more, jadarite’s lithium can be mined easier than existing sources extracted from spodumene.

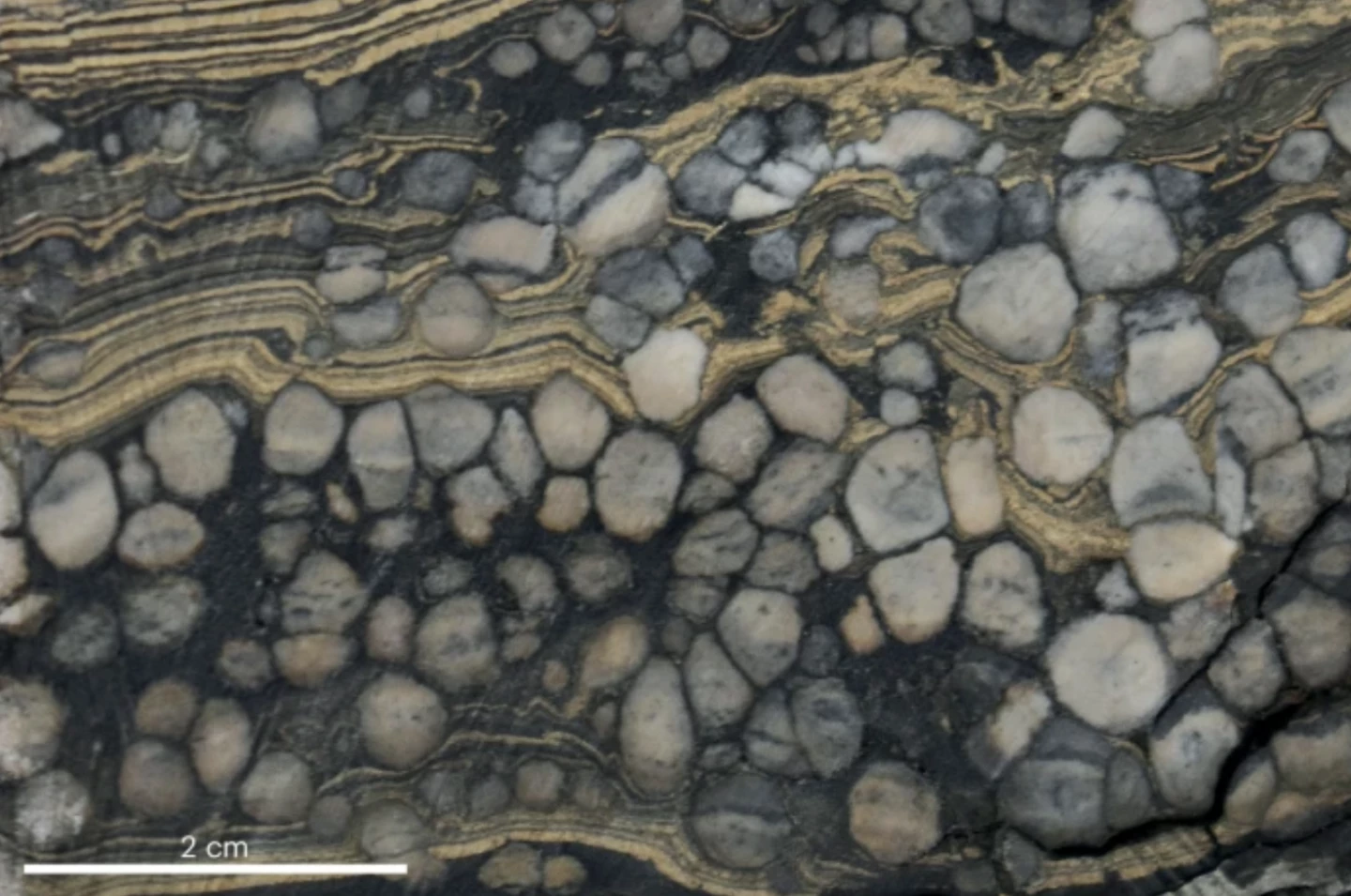

“Jadarite is an economically attractive ore mineral because it holds up to 3.39 wt% lithium and 14.65 wt% boron, the latter of which can be recovered as an extremely useful co-product,” researchers noted. “The lithium content of jadarite is comparable to the mineral spodumene (3.61 wt%), which currently supplies most of the world’s hard-rock lithium; jadarite, however, can be processed using less energy-intensive methods. Jadarite is found as white nodules hosted by dolomitic marls and shales deposited within a closed volcano–sedimentary basin. Such basins are common across the Balkans, with many containing borates and oil shales, but only Jadar has jadarite.”

During the formation of the Jadar Basin, volcanic ash rich in lithium gathered in a shallow lake. Over time, as water evaporated, the area became highly alkaline, which also turned volcanic deposits into gel-like silica. These then kicked off a chain of reactions that led to the jadarite nodules and other minerals forming. In this process, smectite clay was degraded, releasing lithium that would then also form jadarite.

And it’s these unique geological and environmental processes that have made the Jadar Valley the only place, so far, that the mineral has been found.

However, jadarite remains in the ground, where it was first found two decades ago – despite Rio Tinto moving forward with the Jadar Project and a timeline for mining. Environmental impact statements hinted at the scope of damage that the project would likely cause. After nationwide protests, the government canceled mining permits in January 2022, putting the ambitious project on ice. Eighteen months later, the project was revived, but it remains in the planning stage and mining is unlikely to start before 2028 at the earliest (if it gets past the many challenges it faces, both environmental and societal).

The story of jadarite is emblematic of the clean energy paradox we’re now facing: How to mine the minerals needed in order to move away from fossil fuels for a greener future, without simply replacing one destruction for another?

There is some potential good news, though. Last year, scientists detailed how they were able to create a novel synthetic version of jadarite. However, it remains a proof of concept. Nevertheless, this lab-created form of the mineral could help pave the way for alternative lithium materials that bypass current methods of extraction.

While jadarite may never power an EV, it stands as a testament to how rare and extraordinary Earth’s chemistry can be – and a stark reminder that even when pushing for a more green-powered future, there are complex and significant environmental trade-offs to be reckoned with in the process of getting there.

The research was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Source: CSIRO