![]()

This is the first time silicate emission has been detected in planetary-mass objects.

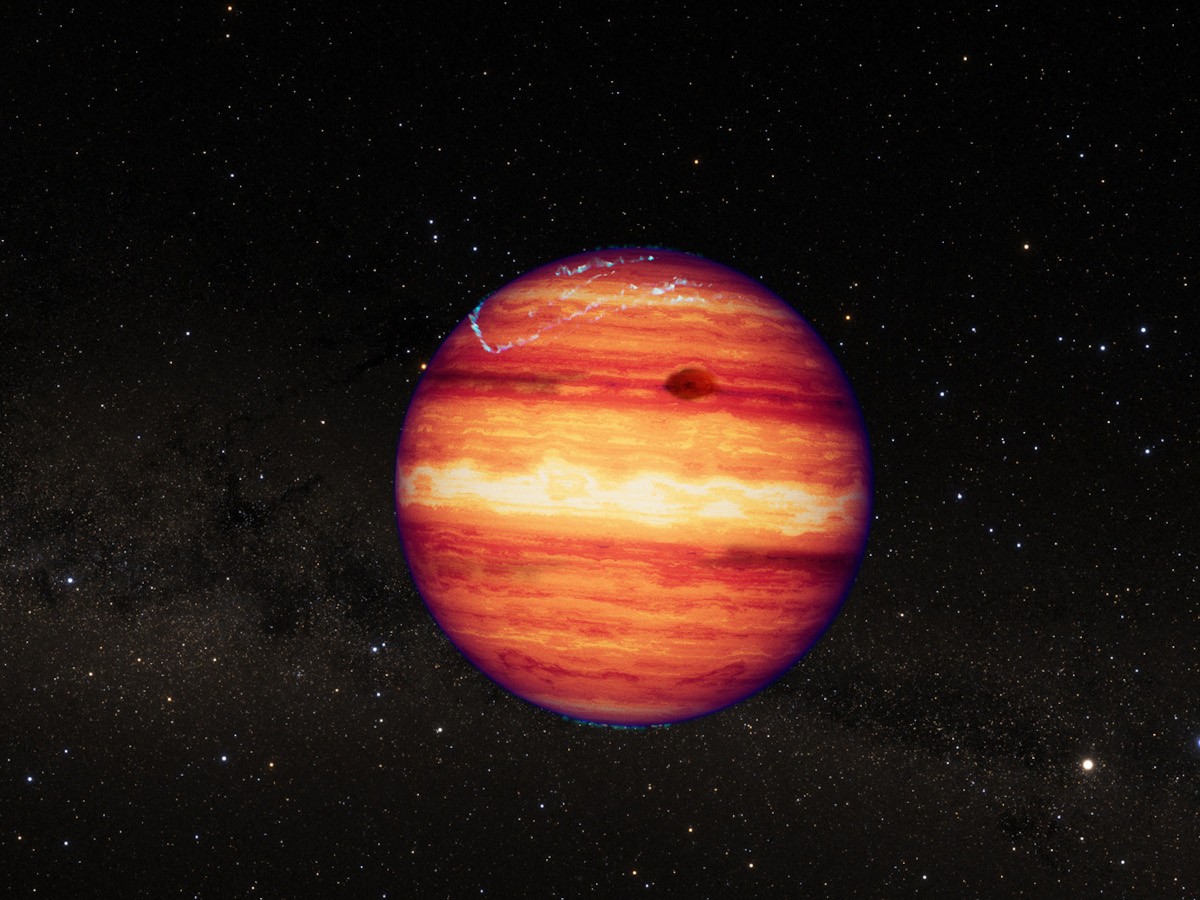

Giant free-floating planets could make their own miniature planetary systems without needing a star to orbit around, finds a new study from Scotland’s University of St Andrews.

Scientists investigated eight young and isolated cosmic objects with masses five to 10 times that of Jupiter using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). For comparison’s sake, Jupiter is around 318 times as massive as Earth.

These objects are comparable to giant planets in their properties, but they don’t orbit around a star. Instead, they float freely in space.

Current research suggests that these are the lowest mass objects formed from the collapse of giant gas clouds, similar to stars. However, unlike stars, these planets do not accumulate enough mass to start any fusion reactions at their cores.

Scientists suggest that some of these free-floating planets could have formed in a similar manner to other planets, in orbit around a star, but later ejected from orbit to float on their own.

These objects are difficult to observe since they are very dim – as they do not emit light – and radiate mostly in the infrared spectrum.

So, in order to study them, the team – made up of researchers from the School of Physics and Astronomy at St Andrews, along with co-authors from Ireland, England, the US, Italy and Portugal – used instruments on the JWST that are extremely sensitive to infrared light. The team analysed detailed spectroscopic observations for these objects that were captured between August and October last year.

Their findings characterise these objects in depth and confirm that they have masses around the same size as Jupiter. Six of them also have excess emission in the infrared spectrum caused by warm dust in their immediate surroundings.

According to the study published last week, these emissions are a sign of protoplanetary disks around the objects, which are generally the birthplaces of planets.

In addition, observations also show emission from silicate grains in these disks, with “clear signs” of dust growth and crystallisation, which is typically the first steps in the formation of rocky planets.

Although silicate emission has been found in stars and brown dwarfs before, this is its first detection in planetary-mass objects.

The latest finding builds on another study published from the University of St Andrews, which showed that disks around free-floating planetary mass objects can last several million years, giving them enough time to form planets.

“Taken together, these studies show that objects with masses comparable to those of giant planets have the potential to form their own miniature planetary systems. Those systems could be like the solar system, just scaled down,” said Dr Aleks Scholz, the principal investigator of the project.

“Whether or not such systems actually exist remains to be shown.”

In another recent study, scientists – for the first time – observed the very early stages of the creation of a new solar system around a baby star.

The newborn planetary system that was just discovered is emerging around Hops-315, a baby star around 1,300 light-years away. Astronomers say that Hops-315 is comparable to the sun.

Don’t miss out on the knowledge you need to succeed. Sign up for the Daily Brief, Silicon Republic’s digest of need-to-know sci-tech news.