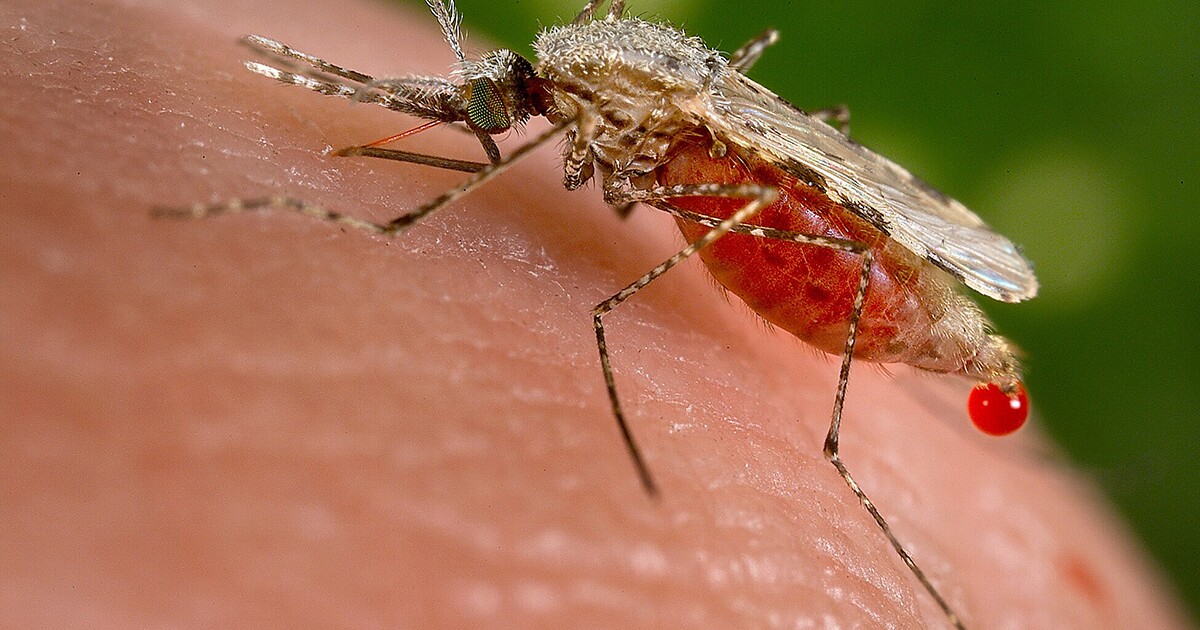

A novel way to prevent the spread of malaria – a potentially life-threatening disease transmitted through bites from mosquitoes infected by a parasite – could soon be realized, thanks to scientists at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) in Australia.

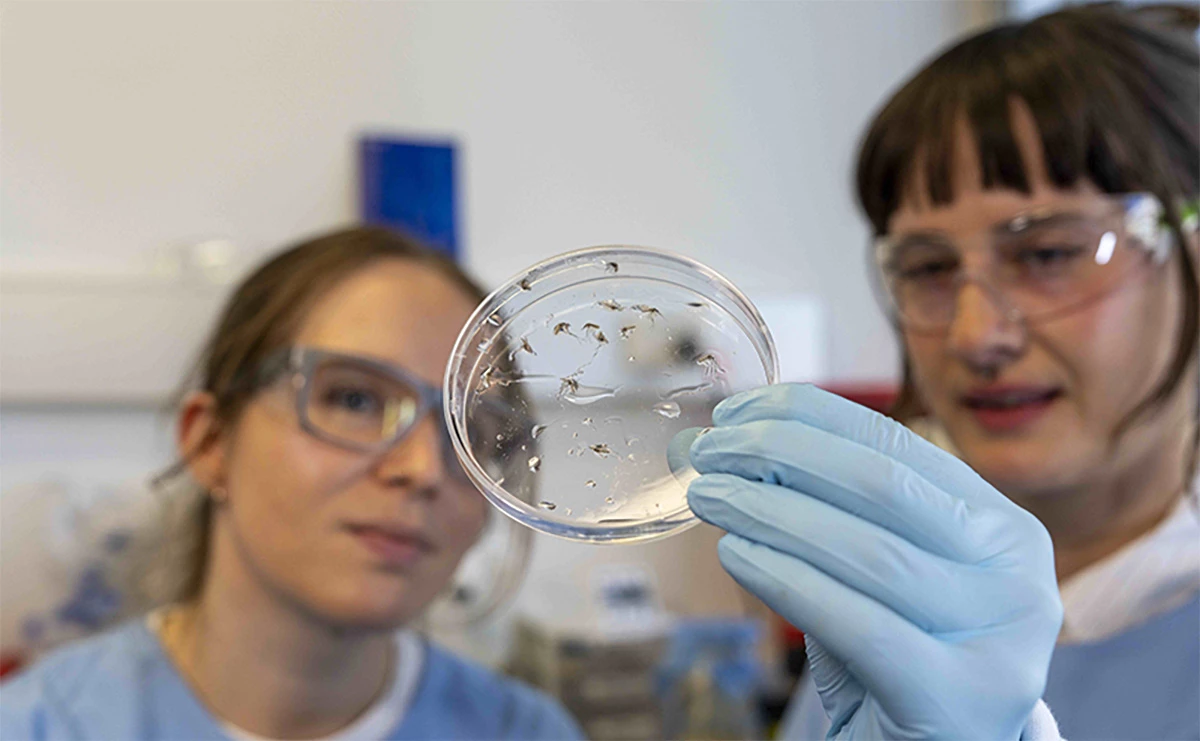

While vaccines for malaria exist and more are being formulated for greater efficacy, the WEHI team went right to the source. It first visualized the protein complex that facilitates the reproduction of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite inside mosquitoes. Then, the scientists developed a mRNA vaccine – based on similar technology used for some COVID-19 vaccines – to block the fertilization process. The result: a 99.7% drop in the rate of transmission of the malaria-causing parasite recorded in preclinical studies.

That could be a huge step forward in the fight against this widespread disease, which affects nearly 300 million people around each year, and claims 600,000 lives annually.

Applying a structural biology approach, the researchers revealed a key connection between two proteins for the parasite’s reproduction in vivid detail for the first time ever.

“Using cryo-electron microscopy, we were able to visualize the full fertilization complex directly from the parasite – not a lab-made version,” lead researcher Dr. Melanie Dietrich explained. “This gave us a clear picture of how this fertilization complex really looks in nature, and revealed a previously unknown region that’s crucial to the process, unlocking a powerful new vaccine target.”

Below is a depiction of the aforementioned proteins Pfs230 and Pfs48/45 bound together. This binding process is crucial for Plasmodium falciparum’s ability to fertilize and spread.

Pfs230-Pfs48/45 fertilisation complex

From there, the researchers created a mRNA vaccine that targeted the contact points revealed in their visualization as responsible for binding those two proteins. High levels of antibodies caused the parasite’s fertilization to fail inside mosquitoes and for its transmission to be blocked.

Naturally, the vaccine has a way to go before it passes stringent clinical trials and becomes commercially available. But it’s a crucial step forward in the battle against malaria, which already has formidable forces working to eliminate it. In India, a new vaccine that’s designed to prevent the parasitic infection in two critical stages has shown promise in the lab, but it’s still in development and is likely 6-7 years away.

At the same time, the first malaria treatment for babies, developed by Novartis, was approved for use last month, and is expected to roll in out in several African countries in a matter of weeks. While malaria treatments for children do exist, this is the first one developed specifically for young babies and small children under 10 lb (4.5 kg). Credit where it’s due: Novartis is slated to introduce the drug on a not-for-profit basis.

Rather than a one-shot solution, the WEHI scientists believe their transmission-blocking vaccine would become part of a multi-stage strategy to combat malaria that target the parasite in mosquitoes and human hosts. It could work in tandem with other vaccines that act on blood or liver stages in people to offer holistic protection against the disease. The team published a paper on its structural biology work in the journal Science last week.

Source: The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research