Type III bursts are usually described as a two-step process: energetic electrons excite Langmuir waves, which are then converted into radio emission near the plasma frequency (Ginzburg & Zhelezniakov 1958). The recent discovery of Fundamental-Harmonic pairs by Parker Solar Probe (PSP) shows that many fundamental type III bursts are weak and composed of short, rapidly varying elements whose intensity rises quickly and then decays more slowly at a fixed frequency (Jebaraj et al. 2023), and PSP observes thousands of such bursts during every close encounter (Pulupa et al. 2025). This raises a conundrum: why are so many of these bursts observed, while a clear positive velocity-space slope expected in the classical bump-on-tail picture is rare (Lin et al. 1981)? This led us to revisit the linear instability responsible for Langmuir waves.

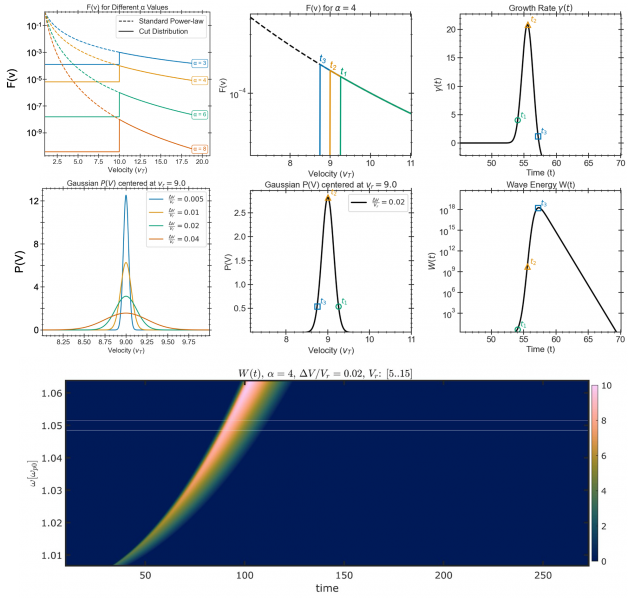

We focus on the front of an impulsively ejected energetic electron population. At a given distance from the source, faster electrons arrive first, and slower ones are still in transit. The mechanism of wave growth due to fast electrons arriving and their consequent absorption by slower electrons was first proposed by Zaitsev et al. (1974). Locally, this manifests as a truncation of the low-velocity side of the energetic tail of the electron distribution (as shown in left-top panel of Figure 1). This moving truncation is enough to linearly drive Langmuir waves, even though the underlying tail would not create a classical positive slope.

The solar wind density is randomly inhomogeneous and small density fluctuations refract and occasionally reflect electrostatic waves, so the waves’ phase velocity fluctuates along their path. Thus, they sample a narrow probability distribution of phase velocities around the phase velocity in homogeneous plasma (Voshchepynets et al. 2015). The center and width of this distribution encode how fluctuations shift and broaden the effective wave–particle interaction. When the front of the electron population sweeps across this resonant band, wave growth rises rapidly; after slower electrons arrive, Landau damping dominates and the waves decay. Scattering of those waves on the same inhomogeneities converts part of the energy into an electromagnetic wave mode around the fundamental plasma frequency, so the radio signal largely inherits the same fast-rise, slower-decay envelope, at least during the growth and early decay. This sequence at a fixed location is summarized schematically in the middle and right panels of Figure 1.

The time-of-flight instability

In Krasnoselskikh et al. (2025), we built a time-dependent linear model at a fixed location. We consider the impulsive injection of an energetic electron tail and account for the time-of-flight truncation at its front. The background random density inhomogeneities are described by a probability distribution for the wave phase velocity. For intuition, we use a narrow, nearly Gaussian distribution and derive a distribution from Gaussian density statistics that allows for both single and occasional multiple reflections on small density humps. This probabilistic description is the core of the model: the local growth rate is the average of the local linear increment over the phase-velocity distribution, and the wave energy follows from integrating that growth in time. The sequence from the truncated tail, through the resonant band, to the resulting growth rate and wave energy is illustrated for a simple Gaussian resonant band in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of the time-dependent instability at a fixed location (adapted from Krasnoselskikh et al. 2025). Top left: energetic-electron distribution $F(V)$ for four different power-law tails. Top middle: power law with index $\alpha = 4$; vertical-coloured lines mark the truncation at the front at three successive times $t_1 < t_2 < t_3$. Bottom left: Gaussian probability distribution $P(V)$ of wave phase velocities centered at the resonant velocity $v_r$, with four different widths and bottom middle panel shows for $\Delta V / V_r = 0.02$; symbols show the relative position of the front at the same three times. Top right: instantaneous linear growth rate $\gamma(t)$, which peaks when the front overlaps the center of the resonant band ($t_2$) and becomes negative once slower electrons dominate ($t_3$). Bottom right: corresponding wave energy $W(t)$, obtained by integrating $\gamma(t)$, showing a rapid rise and slower decay; the symbols $t_1$, $t_2$, and $t_3$ are consistent across all panels. Bottom panel shows the evolution of Langmuir wave spectrum at some given distance, driven by an energetic population of electrons with $\alpha = 4$ and $\Delta V/V_R = 0.02$. The spectrum consists of waves with resonant velocities (in units of thermal velocity), $V_R = 5-15 V_T$.

We map the results at three consequential moments in time. First, the slope of the energetic tail: a shallower tail provides more free energy near the truncation and strengthens growth. Second, the resonant phase velocity: lower resonant velocities produce stronger growth and higher peaks, while higher resonance shifts the action in time and weakens the peak because the front must advance further before it overlaps the resonant band. Third, the fluctuation level: weaker fluctuations produce a narrower distribution, concentrate resonance, and give sharper, larger peaks; stronger fluctuations broaden the distribution, shift the effective resonance toward lower velocities, and reduce and smear out the peak. In all cases, the growth is largest when the front speed crosses the resonant band, the rise is rapid as the overlap builds, and the decay is slower once the slower electrons arrive, and damping prevails. After electrostatic-to-electromagnetic conversion on inhomogeneities, this linear evolution reproduces the asymmetric envelopes observed in the fundamental component. The harmonic remains consistent with standard nonlinear coupling of primary and backscattered Langmuir-like modes and is not considered here.

Why this matters

By shifting attention from a beam with a positive slope to the truncated front of ejected electrons interacting with a fluctuation-broadened resonance, we obtain a simple, linear, and observation-aligned trigger for the fundamental component of Type III bursts. This framework explains the prevalent fast-rise and slower-decay envelopes, is consistent with the scarcity of clear beam signatures in particle data taken at the same times and clarifies why fundamentals measured close to the Sun can be weak or fade by 1 au. It also links measurable burst morphology to ambient fluctuation levels and to the effective resonance of Langmuir waves, providing concrete tests for future PSP and Solar Orbiter observations. The model is intentionally linear and most appropriate for weaker events; it establishes a clear baseline on top of which nonlinear saturation and feedback can be added.

References

Ginzburg, V. L., & Zhelezniakov, V. V. 1958, Sov. Astron., 2, 653.

Jebaraj, I. C., Krasnoselskikh, V., Pulupa, M., Magdalenic, J., & Bale, S. D. 2023, ApJL, 955, L20.

Krasnoselskikh, V., Jebaraj, I. C., Cooper, T. R. F., et al. 2025, ApJ, 990, 100.

Lin, R. P., Potter, D. W., Gurnett, D. A., & Scarf, F. L. 1981, ApJ, 251, 364.

Pulupa, M., Bale, S. D., Jebaraj, I. C., Romeo, O., & Krucker, S. 2025, ApJL, 987, L34.

Voshchepynets, A., Krasnoselskikh, V., Artemyev, A., & Volokitin, A. 2015, ApJ, 807, 38.

Zaitsev, V. V., Kunilov, M. V., Mityakov, N. A., & Rapoport, V. O. 1974, Sov. Astron., 18, 147.