Which animals came first? For more than a century, most evidence suggested that sponges, immobile filter-feeders that lack muscles, neurons and other specialized tissues, were the first animal lineages to emerge. Then, in 2008, a genomic study pointed to a head-scratching rival: dazzling, translucent predators called comb jellies, or ctenophores, with nerves, muscles and other sophisticated features.

That single study ignited a debate that has raged for nearly 20 years, sparking fierce arguments about how complexity evolved in animals. But after dozens of studies — some of which analysed and reanalysed the same data and reached different conclusions — the debate has become entrenched, some researchers say.

“Where it might have been healthy for people to engage with curiosity and an interest in finding the truth together, it became a battle,” says Nicole King, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who co-authored a paper last November that landed cautiously on ‘team sponge.’

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

She has since asked to retract the paper because of flaws identified after its publication, and is reconsidering whether she wants to be part of the debate in the future. Scientists, including King, argue that a different approach is needed: one in which researchers from both sides work together to answer the question.

Fresh ideas — and attitudes — would catalyse progress, they say. “We must think out of the box,” says Leonid Moroz, a neuroscientist at the University of Florida in Gainesville, whose work has supported comb jellies as the lineage at the root of the animal family tree.

The first animals emerge

Around 600 million to 800 million years ago, radically different organisms emerged. Instead of consisting of lone cells, like all previous life did, these creatures were formed of multiple, interacting cells. Multicellularity was so successful that it sparked an explosion in innovative body forms and new ways to sense and respond to environments.

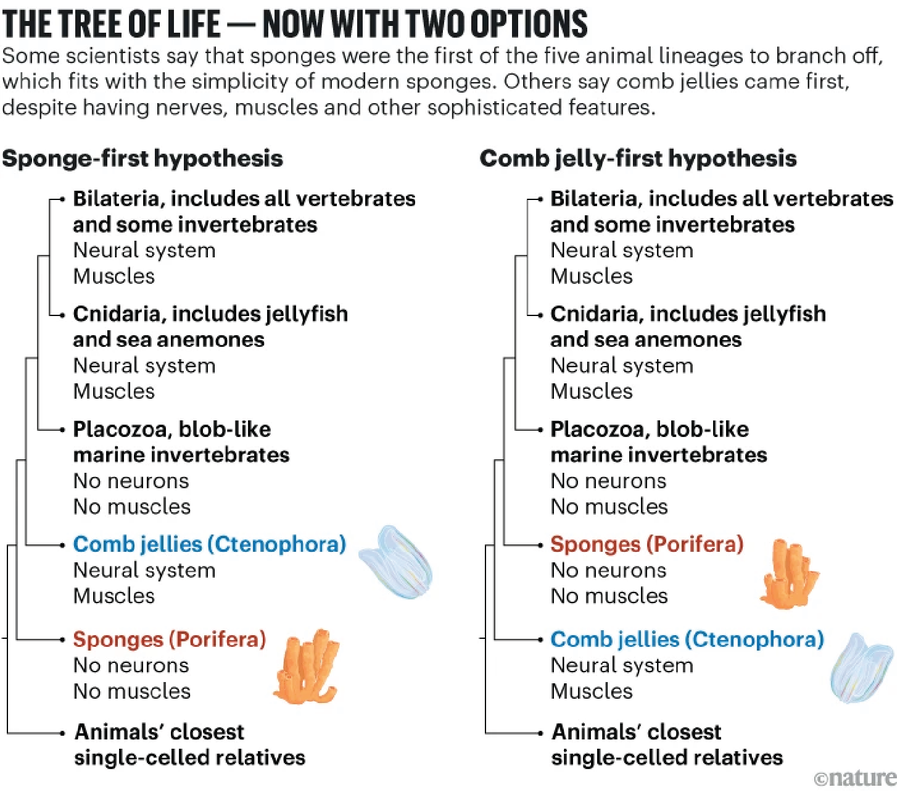

In an evolutionary blink of an eye — perhaps within tens of millions of years — five major groups of animals appeared. As well as the ancestors of modern-day sponges and comb jellies, there were placozoa (now represented by blob-like marine invertebrates); cnidarians (modern members of which include jellyfish and sea anemones); and bilaterians that show mirror-image body symmetry in early development that would give rise to invertebrates, including starfish, snails and spiders, and vertebrates, including humans (see ‘Tree of life — now with two options’).

Nature; Source: “A Sisterly Dispute,” by Maximillian J. Telford et al., in Nature, Vol. 529; January 20, 2016

Fossil evidence of the earliest animals is sparse and hard to decipher — a porous cavity here or a branching tube there. Identifying the first animal lineage, along with knowledge of its modern-day descendants, is another way to gain insight into these early creatures. “Knowing this will tell us something, not everything, about what those first animals might have looked like,” says Max Telford, an evolutionary biologist at University College London. Evolutionary biologists sometimes call this first animal the ‘sister’ to other animal groups, because it shares a common parent with all of them.

For more than a century, most scientists placed the sponge lineage at the base of the animal tree, mainly because modern-day sponges lack many of the features that define other animals, including specialized tissues such as muscle, nerve and gut, which were thought to have evolved later. “If the sponge tree were right, everything would just rather fall into place,” says Telford. But when scientists turned to rapid genome sequencing to confirm this seemingly settled picture, it fell apart.

Evolutionary biology’s epic battle

Casey Dunn, an evolutionary biologist now at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, never planned to kick off a decades-long debate. But the arrival of faster and cheaper DNA-sequencing technologies in the early 2000s inspired Dunn and his colleagues to build the animal tree of life using genome data — one of the first such efforts.

They analysed thousands of gene sequences from 77 organisms — from sponges to sea spiders, and chickens to corals. The study was the first to include comb-jelly genome data, says Dunn, but “going into this we had no idea we would get a result other than sponges are a sister to the rest of animals.” Their 2008 conclusion that comb jellies, not sponges, were the first animal group landed like a bombshell.

The finding drew two kinds of response, says Dunn. One was open-minded curiosity. “Maybe the common wisdom that is in the first few chapters of zoology textbooks isn’t correct,” he says. “There was another response where a variety of folks were like, ‘Hey, sponges have always been the sister and they always will be.’”

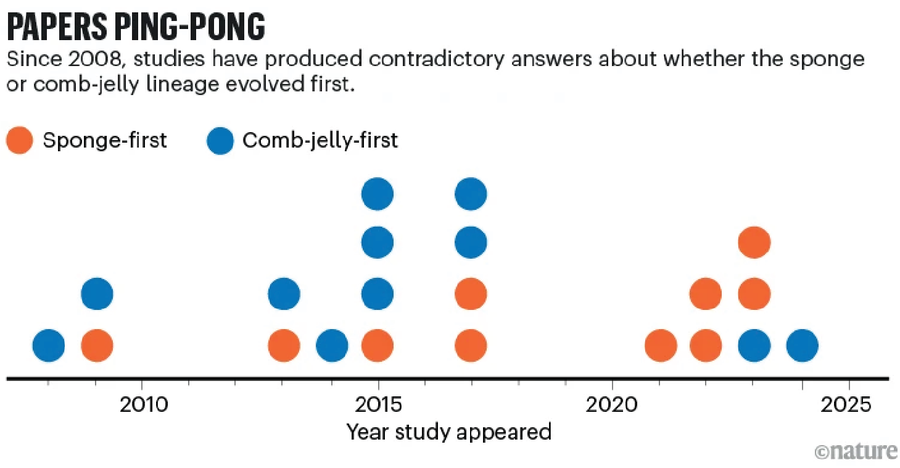

Dozens more papers followed, some using new data sets, different methods of analysis or both. Some gave further support for comb jellies as the lineage at the root of the animal family tree, others re-established sponges as the sister to all other animals (see ‘Papers ping-pong’). Journals published essays, perspectives and other expert analyses, while institutional press releases and media coverage sometimes painted each advance as the final word. “It fell into this sort of back and forth of trying to disprove each other, and then with each subsequent pronouncement saying this is the answer,” says King.

Nature; Source: “Integrative Phylogenomics Positions Sponges at the Root of the Animal Tree,” by Jacob L. Steenwyk and Nicole King in Science, Vol. 390, No. 6774; November 13, 2025

Unlike the sponge-sister hypothesis, which fits neatly with the apparent simplicity of modern-day sponges, putting comb jellies at the root of the animal tree raises new questions. One is how complex tissues such as nerve, muscle and gut could be present in the first animals but absent in members of some later lineages. One possibility is that these tissues evolved not just once, but independently in multiple lineages. Another option is that those features were present in the first animals, but were lost in later lineages, including sponges. Some biologists think that a similar loss occurred in the placozoa lineage, the modern members of which also lack nervous systems and muscles.

The two camps tend to segregate by discipline, observes Antonis Rokas, an evolutionary geneticist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Sponge-sister proponents mostly have backgrounds in zoology and evolutionary-developmental biology. For these scientists, the gradual accrual and elaboration of complex traits was compelling.

Those arguing for a comb-jelly sister, meanwhile, are often trained in genomics, and are more open to the idea that complexity could evolve independently and was routinely gained and lost. Rokas counts himself in this group. “I’m not going to say this is the answer because I’ve been around long enough,” he says.

The struggle to look back

The challenge of piecing together the origin of animals that existed hundreds of millions of years ago using modern-day genome sequences is similar to that faced by astrophysicists discerning the early history of the Universe from the night sky, says Rokas. “The signal is low, it has travelled a long distance and there are multiple things that can erode that signal.”

To determine which of the two lineages — comb jelly or sponge — are at the root of the animal family tree, scientists are hunting for signs of the small number of genetic variations that appeared in a very specific time window: after the first animal lineage diverged and before the next one branched off. These are all that distinguish that first lineage from successive branches before each one starts to follow its own evolutionary path.

But it’s tricky to find this genetic signal. The window might have lasted fewer than five million years, say researchers, less than the time since humans and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) shared a common ancestor, meaning that there wasn’t long for many changes to accumulate. And the signal’s trace faded quickly: after the animal lineages started evolving independently, some 600 million years ago, these early gene variations would have quickly become lost or obscured among newer changes along specific lineages.

When looking for such a weak signal, seemingly minor decisions can exert a major influence on the conclusion. In a 2021 analysis, for example, Rokas and his colleagues found that whether a study comes to a sponge-sister or comb-jelly-sister conclusion can depend on which non-animals — called outgroups — are included in the analysis, as well as various assumptions about how different gene sequences evolve.

“These are good people earnestly trying to get a good answer, but the puzzle is really hard,” says evolutionary biologist Sean Carroll at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Change of tack

To unravel how animals evolved once and for all, many scientists say that fresh approaches are needed. One of the most promising involves inferring evolutionary relationships using the physical position of genes on different chromosomes, instead of using their sequences, as all previous efforts have done. These alterations occur less frequently than sequence changes, and are much less likely to be reversed, leaving potentially indelible marks in the genomes of living organisms.

In a 2023 paper, evolutionary geneticist Darrin Schultz who is now at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, and his colleagues looked at the arrangement of genes across the chromosomes of comb jellies, sponges and other organisms, and found patterns that strongly supported the comb-jelly lineage as the sister to other animals. For example, comb jellies shared numerous chromosome-scale arrangements with single-celled animal relatives. What’s more, these arrangements were absent in sponges, jellyfish and bilaterians.

King says that the Science paper she co-authored in November, which marked her entry into the debate, was an attempt to bring another approach to the problem — but that the need to retract the paper has left her shaken.

Aware that seemingly small decisions about how to analyse the data can influence conclusions, she and her co-author, evolutionary biologist Jacob Steenwyk, also at the University of California, Berkeley, took a ‘kitchen sink’ approach. They analysed new and existing data sets in as many ways as possible to identify sets of genes that were most likely to give consistent answers about whether the sponge or comb-jelly lineage is the sister to the other groups.

Their study supported a sponge sister but said that the debate was far from settled. Scientists on both sides praised its measured tone. “It was great,” says Dunn. But to him, the analysis didn’t add up, so Dunn began corresponding with King and Steenwyk to better understand and reproduce their analysis.

Dunn and several of his colleagues uncovered technical errors, detailed in a letter submitted to Science at the end of December. He says that, when corrected, the data strongly support comb jellies as the first animal lineage. “We definitely screwed up,” says King, who, along with Steenwyk, wrote in a 9 January letter in Science that they intend to retract the study. Science says it will soon publish a formal retraction notice.

King had hoped to help forge a truce between opposing camps. Although she is now likely to move on from searching for the first animal lineage — once her work with Steenwyk, a postdoc in her lab, is complete — she still hopes that ‘team comb jelly’ and ‘team sponge’ researchers will come together to agree on the best approaches and start writing papers together. King says that she wishes she had posted the study as a preprint so that the errors could have been caught sooner. But she had feared a preprint would attract unfair criticism because the debate is so entrenched.

Dunn says that the debate is overblown, however: “More drama has been injected into this question than actually exists.” Responses to Schultz’s 2023 study, suggest that the two sides are far from détente. An article published last December and authored by evolutionary biologist Richard Copley at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Villefranche-sur-Mer challenged the statistical significance of the shared chromosome arrangements that the 2023 study identified and the strength of its conclusion that the comb-jelly lineage diverged first.

Schultz stands by the study — and its approach. But settling the debate might take decades, he says. “For these really hard questions, science evolves slowly.”

More data might help in the nearer term. Rokas says that studies have leaned too heavily on fancy models and theory rather than new data. Very few comb-jelly and sponge species have had their genomes sequenced. Earlier in January, Dunn travelled to Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean — one of the world’s most remote islands — to collect invertebrates including comb jellies.

In the meantime, the quest to find the first animal lineage is leading to discoveries about comb jellies and sponges. For example, says Dunn, studies sparked by the debate have revealed that the comb-jelly nervous system, which lacks neural junctions called synapses, is wildly different from the nervous systems of other animals. “We’re learning so much about these animals,” he says. “People present this as a ping-pong match that’s standing still, but that couldn’t be further from the case.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on January 27, 2026.